.png)

Op. 49

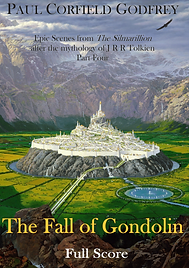

Artwork by kind permission of Ted Nasmith

Volante Opera Productions released a complete commercial demo recording of this work. CDs and scores are available from their website.

The text for The Fall of Gondolin was the most difficult of all the Silmarillion texts to formulate. It was also the text which drew upon the most disparate sources. The first (and the only) complete full-length text was a revision of an even earlier draft made by Tolkien as early as c1920, and never revised; it is this text, with a very antique style, which is included in Volume II of Christopher Tolkien’s edition of The Book of Lost Tales. There then followed a number of abridged versions culminating in the early 1930s with a severely foreshortened text, part of the Quenta Noldorinwa, included in its original form in The Shaping of Middle-Earth (Volume IV of Christopher Tolkien’s History of Middle- Earth). This was the final complete version of the story that Tolkien ever wrote, and forms the basis for the text ultimately published in The Silmarillion in 1977. In the early 1950s, shortly after the completion of The Lord of the Rings, he began to write a newly extended retelling of the story, but this covered only the childhood of Tuor and his journey to Gondolin; the whole of the tale of the fall of Gondolin was therefore missing. Finally he expanded some parts of the earlier history of Gondolin, most specifically the story of Maeglin, and these expansions were also included in the published text of The Silmarillion.

The consequence of this rather fragmentary textual history meant that extreme measures had to be resorted to in order to construct a connected and unified libretto for the musical setting. For the prologue, for example, the chorus sing a poem entitled The Bidding of the Minstrel which was originally written as part of the Tale of Earendel, which Tolkien never ever made any move towards completing; the text in the epilogue was drawn from the same source. But both poems had been subsequently revised several times, and the later revisions at least conformed to the same style as the remainder of the Silmarillion texts which were being employed. But the early Fall of Gondolin text from c1920, written in an altogether different style, formed the only basis for any text for Tuor’s words to Turgon, Turgon’s reply, or the fall of Gondolin itself. There were no other alternatives; and the passages in question had therefore to be subjected to some delicate rewording to remove anachronistic stylistic elements.

The text for the Prologue, as has been noted, came directly from The Bidding of the Minstrel and, apart from cutting, needed no alteration. The final words of the Prologue, spoken by Ulmo to Turgon, came from The Silmarillion. The First Triptych, treating of the story of Maeglin, also came from the same source. Since this was a late addition to the original tale, it required very little revision to fall into line with the remainder of the cycle. It may perhaps be noted that the passage describing the courtship of Eöl and Aredhel, which mirrors the poem Tolkien published in the 1960s as part of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, echoes musically the setting I made in the 1970s of Shadow–Bride as an independent song for mezzo-soprano, viola and piano.

The Second Triptych draws very largely on the “later Tuor ” describing Tuor’s childhood, his meetings with Ulmo and Voronwë, and his journey to Gondolin. The lengthy sections of the 1950s text describing Tuor’s childhood are subject to severe pruning, reduced in effect to the highly compressed account written in the 1930s to form part of the Quenta Noldorinwa text. The encounters with Ulmo and Voronwë, one of the most graphic parts of the later rewriting, are treated at length and form the main substance of Scene Four. Scene Five reverts to an earlier text, The Horns of Ulmo, written even earlier than the original Gondolin text but several times revised; the form used in the cycle is a substantively cut version derived from the 1930s revision quoted in The Shaping of Middle-Earth. In fact even the later revised text refers several times to an earlier version of Tuor’s meeting with Ulmo, where the encounter took place not under the cliffs of storm-swept Vinyamar but in the quiet and peaceful meadows of the Mouths of Sirion; this meant that the cutting had to be carefully shaped to weed out elements at discrepancy with the later version, which of course was the one employed in Scene Four. The remainder of the text of Scene Five and the opening of the Scene Six were drawn directly from the later Tuor, again cut.

The final section of Scene Six, from the entry of Turgon, is the point at which the final rewriting of the later Tuor was abandoned, never to be resumed. The only text here, as has been noted, is that of the 1920s text. Elements were introduced as far as possible from the later Tuor (for example, the quotation of Ulmo’s words) and the remainder was discreetly modernised. But basically this explains the fact that Idril has nothing at all to sing in the First or Second Triptychs; there was no text at all for her to sing!

Nor was there much in what could be used to form a text for the Third Triptych. Here the Quenta Noldorinwa account was curt in the extreme, and provided no text at all for dialogue; and the only version which did was the early Fall, which had both stylistic and narrative divergences. There was nothing available which could be used for a love duet between Tuor and Idril, and it is after all the love between these two which provided the main raison d’être for the whole narrative! Such a desperate problem demanded desperate solutions. The whole of the love duet which constitutes Scene Seven was therefore drawn from a poem written by Tolkien in the 1920s or 1930s which was a Hymn to Eärendil sung by Aelfwine (the later discarded narrator whose original function was to act as a guide to The Silmarillion texts). Eärendil, of course, is not yet born in the original (he is the son of the couple singing the duet); yet the whole context of the poem, a song in praise of the Blessed Realm, is not a wholly unlikely subject for a duet between a couple whose ultimate destiny is to be to dwell in that land. The very brief Scene Eight, the shortest in the whole cycle, is drawn entirely from modernised texts based on the early Fall.

The hymn to Ilúvatar which opens Scene Nine is another alien import. The text is given in full only in early drafts for The Lost Road, Tolkien’s novel of Númenor abandoned in the 1930s; in the final drafts for the novel it is already heavily cut. But the original text is a hymn suitable in most respects to have been sung by the people of Gondolin. The occasional references to Númenor were either cut or substituted with other text. The linguistic discrepancy was more intractable. Tolkien’s Elvish language was a continually evolving and growing thing, and only became more ossified after the publication of The Lord of the Rings in 1954, which meant that defined texts were finally established. But the 1930s Elvish used in the hymn was considerably different from that used in the later post-1954 text, which also included the Elvish hymn to be used in the epilogue. I made some very desultory efforts to regularise some of the spellings (Anor for Anar , Ithil for Isil ) to bring them into line with the Elvish words (Sindarin rather than Quenya) which readers of The Lord of the Rings might anticipate. But other discrepancies inevitably remained; my only consolation would be that Elvish of any variety is not a language in common use among choral societies or concert audiences.

The remainder of the text for Scene Nine consists of sections of modernised dialogue drawn from the early Fall and two brief passages of narrative drawn from the Quenta Noldorinwa. The text for the Epilogue is somewhat different. The foreground text, Idril’s farewell to Tuor and his departure over the Sea, is in fact in direct contradiction to the story (where Idril sails to the Blessed Realm with Tuor) given by Tolkien in all the manuscripts after 1926. But the text comes from an earlier tradition, and the poem, The Happy Mariners, although given in a quite late revision probably intended for publication in the 1960s, was originally called The Sleeper in the Tower of Pearl, and formed part of the Tale of Earendel abandoned in the 1920s. And there the story was quite definitely that Tuor left Idril behind when he sailed for the Blessed Realm; indeed, one of the notes for The Tale of Earendel identifies the singer of the song with Idril herself. And the singer of The Happy Mariners, whoever they may ultimately have been, refers quite specifically even in the latest revisions to Gondobar, a name which Christopher Tolkien correctly observes is only ever used as another name for Gondolin and which has therefore no significance to the later story and is otherwise inexplicable. It is on that admittedly rather indefinite basis that I have made the dramatic alterations to the epilogue which form the final text, but which do in their own way echo Sam Gamgee standing alone on the shores of Middle-Earth at the end of The Lord of the Rings where Frodo makes his own similar journey across the Sea.

The Elvish poem which is sung simultaneously in the distance is, of course, the same as the voices Frodo hears on his voyage. The text, apart from its relation to the Sea, has no connection with Gondolin at all. It was published as part of Tolkien’s book of essays The Monsters and the Critics and in fact relates to the Fall of Númenor, some three thousand years in the future in the history of Middle-Earth. But it does describe the journey of a lonely ship across the Ocean; and its final words, “Who shall see the last morning?”, chimes in perfectly with the song of the abandoned Sleeper in the Tower of Pearl, Idril, who looks in vain across the water seeking sight of the Blessed Realm.

It will be noted that the final text for The Fall of Gondolin, apart from a fleeting mention in the very first bars of the Prologue, contains no reference to Eärendil as the son of Tuor and Idril, and as the messenger to the Valar whose mission will bring about the War of Wrath and the ultimate fall of Morgoth. The tale of Eärendil, indeed, should be the last part of any complete Silmarillion cycle. But, apart from Bilbo’s song in the house of Elrond contained in Book II of The Lord of the Rings, various fragmentary drafts from the 1920s which in any case refer to a totally different version of the story, and several other tangentially connected poems most of which had already been cannibalised to serve as text for The Fall of Gondolin, it seemed to me at the time of writing that there was no material whatsoever to work on, and that some elision was therefore essential to bring the incomplete cycle to a required conclusion. It might be implied that it was Tuor ’s mission to the Blessed Realm which brought about the intervention of the Valar and the destruction of Angband; it might be suspected that the fall of the Balrog saved the Elves from further war; it might be supposed that the fate of the Silmarils was other than Tolkien’s late additions to the Quenta made explicit. Those who knew Tolkien’s work would not be misled. Those whose knowledge extended no further than The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings would hopefully be satisfied. And those who understood the problems would possibly forgive.

But since I came to this determination in 1998, I subsequently returned to Bilbo’s Lay of Eärendil in a full-length song setting for tenor and orchestra using a text incorporating revisions apparently made by Tolkien himself after the publication of the version in The Fellowship of the Ring; and then, as will be seen, eventually wrote the final segment of the cycle in the form of The War of Wrath, bringing the whole to a conclusion of a very different nature. Those issues are explored further in the introduction to The War of Wrath itself.

PAUL CORFIELD GODFREY

Orchestra

3 Flutes (3rd Flute doubling Piccolo)

4 Recorders (playing 4 Sopranino, 2 Descant, 2 Treble and 2 Tenor Recorders)

2 Oboes

English Horn

2 Clarinets

Bass Clarinet

3 Bassoons (3rd Bassoon with extension to play low A)

4 Horns

3 Trumpets

2 Tenor Trombones

Bass Trombone

Tuba

Timpani

Three Percussion Players (Side Drum, Bass Drum, Tamborine, Cymbals, Triangle, Jingles, Gong, Xylophone, Glockenspiel, Vibraphone, Tubular Bells, Deep Church Bells, Wind, Thunder)

Pianoforte (doubling Celesta)

Harp

12 First Violins

12 Second Violins

8 Violas

8 Violoncellos

6 Double Basses

Characters

Valar:

ULMO (Bass-Baritone), the Lord of the Waters

MORGOTH (Bass), the Enemy

Elves:

TURGON (Bass), King of Gondolin

IDRIL (High Soprano), his daughter

AREDHEL (Mezzo-soprano), his sister

EÖL (Baritone), a Dark Elf

MAEGLIN (Baritone), son of Aredhel and Eöl

ECTHELION (Baritone), Captain of the Guard of Gondolin

VORONWË (Baritone), an Elf of Gondolin

Men:

TUOR (Lyric Tenor) son of Huor

Half-Elven:

EÄRENDIL (Silent), child of Tuor and Idril

Mixed chorus Unseen Voices and people of Gondolin

Synopsis

The Bidding of the Minstrel (Prologue)

The Chorus sings of the deeds of Eärendil the seafarer, which have now receded into the mists of memory. Ulmo, the Lord of Waters, appears to the Elvenking Turgon and bids him to lay down his arms and shows him the location to build the Hidden City of Gondolin.

Eöl, kin of Thingol, has settled in the outlying woods of Nan-Elmoth near to Doriath. As payment for being given leave to live there he begrudgingly creates the black sword Anglachel. His malice is poured into the blade and Melian warns her husband to never use it.

The Foundation of the Hidden City (Scene One)

The fair city of Gondolin is built. Turgon dwells there with his daughter Idril Celebrindal and his sister Aredhel. Turgon has decreed that no one who knows the city’s location may depart. Aredhel, wearying of the delights of Gondolin, informs her brother that she intends to leave the city.

The Birth of Maeglin (Scene Two)

Aredhel is captured by the Dark Elf Eöl, who takes her as his wife. She bears him a son, Maeglin, who grows to have little love for his father and his ways. Maeglin asks his mother to lead him to Gondolin away from his father’s tutelage. She consents and the two flee their bondage.

The Return to Gondolin (Scene Three)

Aredhel and Maeglin travel to Gondolin, but, unbeknownst to them, are followed by Eöl. Turgon welcomes the return of Aredhel and offers Maeglin a high position in the realm. Ecthelion, the Captain of the Guard, enters to inform Turgon that another has come unbidden to the Gate. Aredhel admits to her brother that the newcomer is her husband and begs him to stay his hand. Turgon welcomes Eöl into his city and his family, but informs him that now he has entered Gondolin he must remain there. Eöl is determined to leave and to take his family away with him. Turgon gives him and his son a choice: stay or die. Eöl chooses the latter and attempts to kill his son with a spear. Aredhel steps between her husband and son, intercepts the blow and is killed. Eöl is condemned and thrown from the ramparts of the city. Idril approaches Maeglin to console him but something in his gaze frightens her. She leaves him alone.

At this time the second born children of Illúvatar start to awaken, the Race of Men. Morgoth attempts to corrupt them to his cause but many resist and join forces with the Elves to try and rid Middle-Earth of his influence.

The Messenger (Scene Four)

We are introduced to Tuor, the son of Huor, the brother of Húrin, who died in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears. Tuor journeys to the shores of the ocean, where a great wave arises and brings Ulmo with it. Ulmo addresses Tuor and bequeaths to him the former arms of Turgon and a mission: to be his messenger and warn Turgon that the fall of Gondolin draws near. Ulmo saves a wrecked ship from the sea and upon it is Voronwë, an Elf of Gondolin, who was sent by Turgon on a failed mission to seek aid from the Blessed Realm. Voronwë and Tuor discuss the errand that Ulmo has set. Voronwë describes to Tuor his labours in the sea and finally agrees to take him to the Hidden City.

The Horns of Ulmo (Scene Five)

Tuor tells Voronwë of his vision of Ulmo and his errand as they continue their journey to Gondolin. Voronwë leads Tuor to the dark and concealed Gates of the City. They are challenged at the Gate by Ecthelion.

The Message (Scene Six)

Ecthelion refuses the pair entry into Gondolin until Tuor removes his cloak and reveals the arms of Turgon, bequeathed to him by Ulmo. Turgon, Idril and Maeglin greet the visitors. When Tuor imparts the message of Ulmo to the King he refuses to abandon his city. Tuor, now trapped within the city, is left behind with Idril who offers him aid. This is much to the dismay of the on looking Maeglin, who is himself enamoured of Idril.

The Wedding of Tuor and Idril (Scene Seven)

Tuor and Idril are married and have a baby son Eärendil. As their child grows so too does their love but they are being watched by the jealous Maeglin. The couple both have a yearning to be beyond the City gates and to see the Blessed Realm.

The Betrayal (Scene Eight)

Maeglin is brought before Morgoth, where he offers to betray the whereabouts of the Hidden City if he is rewarded.

The Fall of Gondolin (Scene Nine)

The City of Gondolin is celebrating the first morning of summer and all sing an Elvish hymn to Ilúvatar. It is at this point that Morgoth looses his whole force against Gondolin. Turgon, realising his folly at not heeding the words of Ulmo, tells his people to flee and follow Tuor as their leader. The King remains behind, refusing to strike any blow and sends a reluctant Ecthelion after them. Maeglin attempts to seize Idril and Eärendil. Tuor struggles with him and casts him from the walls to the same death as his father before him. A sudden burst of flame from below rises and engulfs Turgon and from it rises a Balrog. Ecthelion rushes forward and hurls himself at the Spirit of Flame, and both fall to their death in the abyss. Tuor and Idril lead the survivors away from the fallen city and down towards the sea.

The survivors of all of the great realms of Beleriand, Nargothrond, Gondolin and Doriath, along with the remaining members of the great Houses of Men are now isolated on the Western Coast of Middle-Earth, the majority in the Havens of Sirion, where Tuor acts as Lord of the Exiles. The rest of the land is now taken by Morgoth’s forces and the war against him is all but lost.

The Last Ship (Epilogue)

A now aged Tuor bids his wife and adult son farewell as he boards a ship. His aim is once more to sail the ocean and seek the Blessed Realm.

Libretto

Text by J R R TOLKIEN

extracted from The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, The Book of Lost Tales, The Shaping of Middle-Earth, The Lost Road

and The Monsters and the Critics (edited by C R Tolkien)

used by kind permission of the estate of the late John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and HarperCollinsPublishers

by

PAUL CORFIELD GODFREY ©2021

The Bidding of the Minstrel (Prologue)

The Curtain rises into darkness: a dim light as of mist on the sea slowly becomes visible.

UNSEEN VOICES

Sing us a tale of Eärendil* the wandering,

chant us a lay of his white-oared ship,

more marvellous-cunning than mortal man’s pondering,

foamily musical out on the deep.

Sing us a tale of immortal sea-longing

the Eldar once made ere the change of the light,

weaving a wine-like spell, and a burning

wonder of spray and the odours of night;

gallantly bent on measureless faring,

ere he came homing in sea-laden flight,

circuitous, lingering, restlessly daring,

coming to haven unlooked for, at night.

But the music is broken, the words half-forgotten,

the sunlight has faded, the moon is grown old,

the elven-ships foundered or weed-scathed and rotten,

the fire and the wonder of hearts is grown cold.

Who now can tell, and what harp can accompany

with melodies strange enough, rich enough tunes,

pale with the magic of cavernous harmony,

loud with shore-music of beaches and dunes?

The song I can sing is but shreds one remembers

of golden imaginings fashioned in sleep,

a whispered tale told by the withering embers

of old things far off that but few hearts keep.

The scene darkens and the sea mists vanish; the Elvenking Turgon is seen, and through the darkness is heard a voice.

The voice of ULMO

Now shalt thou go to Gondolin, Turgon;

and I will maintain my power in the vale and all the waters therein,

so that none shall mark thy going,

nor any find there the hidden entrance against thy will.

But love not too well the works of thy hands and the devices of thy heart;

and remember that the true hope of the Elves lieth in the West,

and cometh from the Sea.

Turgon removes his armour, lays down his arms and leaves them behind.

* THE PROHPECY OF EÄRENDIL: “One day a messenger from Middle-Earth will come through the shadows to Valinor, and Manwë shall hear, and Mandos relent.” This is the prophecy that a representative of the two kindreds of MIDDLE-EARTH will find a way to VALINOR to plead for aid in the war against MORGOTH. This prophecy comes to fruition in “The War of Wrath” but here, in “The Fall of Gondolin” we see ULMO assembling all of the circumstances to prepare for his coming.

The Foundation of the Hidden City (Scene One)

Slowly the scene is revealed: the highest platform of the Tower of the King in the Hidden City of Gondolin*.

UNSEEN VOICES

And Turgon rose, and went with his household silently through the hills,

and passed the gates in the mountains, and they were shut behind him.

But behind the mountains the people of Turgon throve,

and they put forth their skills in labour unceasing, and Gondolin became fair indeed.

High and white were its walls, and smooth its stairs,

and tall and strong was the Tower of the King.

There shining fountains played,

and in the courts of Turgon stood images of the Trees of old.

But fairest of all the wonders of Gondolin were Idril, Turgon’s daughter,

that was called Celebrindal; and Aredhel his sister, the White Lady.

The light which has slowly been growing now reveals Turgon seated on his throne with Aredhel at his side.

UNSEEN VOICES

But Aredhel wearied of the Guarded City,

desiring ever the longer the more to ride again

in the wide lands and to walk in the forests;

and when years had passed, she spoke to Turgon and asked leave to depart.

TURGON

Go then if you will, though it is against my wisdom;

and I forebode that ill will come of it, both to you and me.

AREDHEL

I am your sister and not your servant,

and beyond your bounds I will go as seems good to me.

And if you begrudge me an escort, then I will go alone.

TURGON

I grudge you nothing that I have.

Yet I desire that none shall dwell beyond my walls who know the way hither;

and if I trust you, my sister, others I trust less to keep guard on their tongues.

Aredhel turns away from him with a gesture of contempt, and leaves the hall. Turgon sinks down into his throne in despair. At once the stage begins to darken, and increasingly the shadows of a dark and tangled forest are cast across the scene.

UNSEEN VOICES

So Aredhel rode abroad, seeking for new paths and untrodden glades;

and she walked in the twilight of Middle-Earth when the trees were young,

and enchantment lay upon it still.

* GONDOLIN: We hear at this point three distinct themes for Gondolin itself: first an archaic-sounding melody which looks back to the heritage of the city, then a brief series of shifting chords which tell of its hidden nature, and finally a new rising theme which looks to its future as a symbol of hope to those resisting Morgoth.

The Birth of Maeglin (Scene Two)

UNSEEN VOICES

But the trees of Nan Elmoth* were the tallest and darkest in all the world,

and there the sun never came;

and there Eöl dwelt,

loving the night and twilight under stars.

And so it came to pass that Eöl,

the Dark Elf living in deep shadow,

saw Aredhel as she strayed among the tall trees,

and he desired her;

and he set his enchantments about her,

so that she draw ever nearer to the depths of the wood.

And when, weary with wandering, Aredhel came to him,

he welcomed her and led her into his dwelling.

And there she remained; for Eöl took her to wife,

and it was long ere any heard of her again.

And they wandered far together

by the light of the sickle moon, or under the stars.

And Aredhel bore to Eöl a son in the shadows of Nan Elmoth,

and he called him Maeglin,

which is, The Sharp Glance.

The lights have indicated the passing of the years. Eöl now is seen again, standing on the edges of the wood with Aredhel by his side. Here also now stands the young Maeglin, looking out with yearning beyond the borders of the forest. As the light becomes stronger it becomes clear that an argument is in progress.

EÖL

You are of the House of Eöl, Maeglin, and not of Gondolin.

All this land is my land,

and I will not deal nor have my son deal with the slayers of my kin,

the invaders and usurpers** of our homes!

He storms away into the darkness of the forest; Maeglin turns with eagerness towards his mother.

MAEGLIN

Lady, let us depart while there is time!

What hope is there in this wood for you or me?

Here we are held in bondage,

and no profit shall I find here.

Shall we not seek for Gondolin?

You shall be my guide, and I shall be your guard!

She flings her arms around him. Eöl, returning out of the forest, sees them disappear into the distance and sinks down onto the ground.

* NAN ELMOTH: This is the first description of a dangerous ancient forest which was to haunt Tolkien’s later writings, and the music draws on the same material as the Old Forest in Tom Bombadil. There are also references to the poem Shadow-Bride where Tolkien wrote of a woman enchanted by a lover who binds her to himself. Here the consequences will lead directly to the destruction of Gondolin itself.

** INVADERS AND USURPERS: Here EÖL is referring not only to the KINSLAYING but also the arrival of the NOLDOR in MIDDLE-EARTH where they took up residence, establishing their own realms and claiming new lands.

The Return to Gondolin (Scene Three)

The scene slowly changes back to the Tower of Gondolin as in Scene One, with Turgon seated on his throne.

UNSEEN VOICES

And, driven by anger and despair,

Eöl rode hard upon the way that they had gone before;

and Aredhel and Maeglin came to the Gate of Gondolin

and the Dark Guard under the mountains.

Aredhel and Maeglin are led in before the King; both are dressed in fair and lordly garments and have put aside the travel-worn cloaks.

TURGON

I rejoice indeed that my sister has returned to Gondolin;

and now more fair again shall my city be than in the days when I deemed her lost.

And Maeglin shall have the highest honour in my realm.

ECTHELION [enters the hall below in great haste]

Lord, the Guard have taken captive one that came by stealth to the Dark Gate*.

Eöl he names himself, and he is a tall Elf dark and grim;

yet he names the Lady Aredhel as his wife, and demands to be brought before you.

His wrath is great and he is hard to restrain;

but we have not slain him as your law demands.

AREDHEL [aside to Maeglin]

Alas! Eöl has followed us, even as I feared. But with great stealth was it done;

for we saw and heard no pursuit as we entered upon the Hidden Way**.

[to Turgon] He speaks but the truth.

He is Eöl, and I am his wife, and he is the father of my son.

Slay him not, but lead him hither to the King’s judgement, if the King so wills.

Turgon nods his consent to Ecthelion, who gives a signal to his guards. Eöl is brought in wearing his travelling garments. Turgon rises from his throne and descends to meet him, extending his hands in token of friendship.

TURGON

Welcome, kinsman; for so I hold you.

Here you shall dwell at your pleasure,

save only that you must here abide and depart not from my kingdom;

for it is my law that none who finds his way hither shall depart.

EÖL

I acknowledge not your law.

No right have you or any of your kin in this land

to seize realms or to set bounds, either here or there.

I care nothing for your secrets and I came not to spy,

but to claim my own: my wife and my son.

Yet if in my wife you have some claim, then let her remain;

let the bird go back to her cage,

where soon she will sicken again as she sickened before.

But not so Maeglin. My son you shall not withhold from me.

Come, Maeglin son of Eöl! Your father commands you.

Leave the house of his enemies and the slayers of his kin, or be accursed!

Turgon turns with enquiry to look at Maeglin, but the latter stands still as if rooted, and makes no sign.

TURGON

I will not debate with you, Black Elf.

By the swords of the Eldar alone are your sunless woods defended.

Your freedom to wander there wild you owe to my kin;

and but for them, long since you would have laboured

in thraldom in the pits of Angband.

And here I am King, and my doom is law.

This choice only is given to you: to abide here, or to die here:

and so also for your son.

Eöl stands long without word or movement, while a still silence falls upon the hall. Suddenly he throws back his cloak and brings forth a javelin.

EÖL

The second choice I take, and for my son also! You shall not hold what is mine!

Aredhel springs before Maeglin as Eöl casts the javelin, and the dart takes her in the breast. Those standing by seize Eöl and hold him fast; Maeglin standing below Turgon looks at his father and remains silent.

EÖL

So! you forsake your father and his kin, ill-gotten son!

Here shall you fail of all your hopes, and here may you yet die the same death as I***.

Ecthelion leads Eöl to the back, and they cast him over the precipice behind the throne which rises sheer above the valley. Many others bear the body of Aredhel away; Maeglin alone remains, looking out over the vale below. Idril comes to him, and touches him by the hand; Maeglin draws back in surprise and looks into her eyes. Idril starts back slightly, and then, recovering herself, follows after Aredhel’s bier. Maeglin remains alone, looking after her.

The Curtain falls.

* THE DARK GATE: The outer gates to the city.

** THE HIDDEN WAY: The hidden passage through the mountains that leads to the gate.

*** “THE SAME DEATH AS I”: The theme associated with heritage of Gondolin, here transformed into a heavy funereal march, is interrupted by a plunging descent which will return at the very moment when Maeglin himself is thrown from the walls during the fall of the city.

The Messenger (Scene Four)

The scene opens into the mists as in the Prologue.

UNSEEN VOICES

Huor the brother of Húrin was slain in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears*;

and in the winter of that year Rian his wife bore her child in the wilds,

and he was called Tuor.

And when Tuor had lived thus in the hills for three and twenty years,

Ulmo set it in his heart to depart from the house of his fathers;

and at last unawares he came to the black brink of Middle-earth,

and saw the great and shoreless Sea.

The mists part, and a high clifftop is seen looking down over a vast ocean. On the top of the cliff stands Tuor, and he stretches out his arms as if to encompass the horizon, breathing the sea air.

UNSEEN VOICES

And at that hour the sun went down beyond the rim of the world, as a mighty fire.

And it grew cold, and there was a stir and a murmur as of a storm to come.

And it seemed that a great wave arose, and upon it lay a mist of shadow.

Then, as it drew near and rushed closer,

there stood dark against the rising storm a shape of great height and majesty.

The storm now rises even higher, and the shape of Ulmo rises from the waters above it. Tuor has remained throughout the foregoing alone upon the cliff with outspread arms; now he sinks in awe to his knees.

ULMO

Rise, son of Huor! for now shalt thou walk under my shadow.

Haste thou must learn, for in the fires of Morgoth thy goal will not long endure.

TUOR

What then is my goal, Lord?

ULMO

To find Turgon, and to look upon the Hidden City.

And I shall array thee as my messenger,

even in those arms which long ago I decreed for thee.

The shape of Ulmo raises his left hand; and below on the cliff appears Turgon’s great suit of golden mail and a helm. Tuor raises himself and walks to the cliff, and girds himself.

TUOR

By this token I will take these arms, and upon myself the doom that they bear**.

ULMO

But in the armour of Fate there is ever a rift,

and in the walls of Doom a breach, until the End.

And now the Curse of Mandos*** hastens to its fulfilment,

and all the works of the Eldar shall perish.

The last hope alone is left,

the hope they have not looked for and have not prepared.

And that hope lieth in thee; for so I have chosen.

TUOR

Then shall Turgon not stand against Morgoth, as all yet hope?

And of little avail shall I be,

a mortal man alone among so many and valiant of the High Folk of the West.

ULMO

It is not for thy valour along that I send thee,

but to bring into the world a hope beyond thy sight****,

and a light that shall pierce the darkness.

Go now, lest the Sea devour thee!

And I will send one to thee out of the storm, and thus shalt thou be guided.

TUOR

I go, Lord! yet now my heart yearneth rather to the Sea.

Ulmo raises his right hand, and the storm crashes forward onto the land. Tuor clambers back to the top of the cliff, while the shape of the Valar vanishes into the darkness. The storm rages***** across the scene with increasing violence, and Tuor crouches down beneath its fury. In the distance it appears that a ship is driven forward onto the rocks and founders. Slowly the storm dies down and a cold dawn steals quietly across the shore. Tuor rises and looks across the sea, and then calls in a loud voice.

TUOR

Hail, Voronwë! I await you******.

VORONWË [a tall dark Elf, clad in a travel-stained cloak, rises from the shore by the wrecked ship and clambers up towards Tuor]

Who are you, lord? Long have I laboured in the unrelenting Sea;

is the Shadow overthrown? Have the Hidden People come forth?

TUOR

Nay, the Shadow lengthens, and the Hidden remain hid.

VORONWË

But who are you?

For many years ago my people left this land, and none have dwelt here since.

And now I perceive that despite your raiment you are not of them as I thought,

but are of the kindred of men.

TUOR

I am. And are you not the last mariner that sought the West from the Havens?

VORONWË

I am. Voronwë son of Aranwë am I.

But how you know my name and fate I understand not*******.

TUOR

The Lord of Waters spoke to me, and sent you hither to be my guide.

VORONWË

Then great indeed must be your worth and doom!

But whither should I lead you, lord?

TUOR

I have an errand to Turgon, the Hidden King.

There doom will strive with the counsel Ulmo.

Will Turgon forget that which he spoke to him of old:

“Remember that the true help of the Elves lieth in the West,

and cometh from the Sea?”

VORONWË [turns away and looks out across the Sea]

Often have I vowed in the depths of the Sea

that I would dwell at rest far from the Shadow in the North,

where spring is sweeter than the heart’s desire.

But if evil has grown while I have wandered,

and the last peril approaches,

then I must go to my people.

TUOR

Then we will go together, as we are counselled.

But whither will you lead me, and how far?

VORONWË

You know the strength of men;

yet how think you that I could labour countless days in the salt waters of the sea?

But the Great Sea is terrible, Tuor son of Huor;

and it works the Doom of the Valar.

Worse things it holds than to sink into the abyss and so perish:

loathing, and loneliness and madness;

terror of wind and tumult, and silence and shadows where all hope is lost

and all living things pass away.

And many shores evil and strange it washes,

and many islands of danger and fear infest it.

But very bright and clear were the stars upon the margin of the world********,

when at times the clouds about the West were drawn aside.

Yet whether we saw only clouds still more remote,

or glimpsed indeed the mountains

about the long strands of our lost home, I know not.

Far, far away they stand,

and none from mortal lands shall come there ever again, I deem.

TUOR

Mourn not, Voronwë.

For my heart says to you that far from the Shadow your long road shall lead you,

and your hope shall return to the Sea.

VORONWË

And yours also. But now we must leave it, and go in haste.

They rise and pull their cloaks about them. The scene darkens.

* THE BATTLE OF UNNUMBERED TEARS: During this disastrous battle, the forces of ELVES and MEN almost succeeded in a direct attack on the doors of ANGBAND but were eventually outmatched by MORGOTH’s forces who aided by treachery forced them back. It was in this battle that GWINDOR and HÚRIN were captured and imprisoned. The music of the prelude refers back to the theme associated with the House of Hador in The Children of Húrin.

** “BY THIS TOKEN”: The archaic-sounding theme associated with the heritage of Gondolin now becomes definitively associated with the destiny planned for TUOR as the messenger of the VALAR and specifically ULMO.

*** THE CURSE OF MANDOS: The theme of MANDOS here returns for the first time since Beren and Lúthien, as the fate of the NOLDOR once again moves to the forefront of the action.

**** THE LAST HOPE: ULMO is being deliberately vague here. He knows that it is unlikely that TURGON will agree to leave the city. The “hope beyond thy sight” and “light that shall pierce the darkness” is, unbeknownst to TUOR, a reference to EÄRENDIL, the as yet unconceived son of TUOR and TURGON’s daughter IDRIL.

***** THE VISION OF TUOR: During the storm ULMO reveals to TUOR a vision of the history of Middle-Earth and his part in it, which he will endeavour to describe in the next scene.

****** THE MESSENGER OF ULMO: TUOR’s first line here after his conversation with ULMO and his commands to ECTHELION and TURGON in Scene Six have a special significance as they are the words of ULMO being spoken through the mouth of TUOR. This is a difficult thing to represent on stage, but that is why, especially in Scene Six, TUOR speaks in a much more commanding tone and seems to stand in defiance before the mighty King of GONDOLIN.

******* VORONWË’S MISSION: When the war against MORGOTH is starting to turn against the ELVES TURGON, in secret, sent forth mariners from GONDOLIN to reach the western shore of BELERIAND and attempt to cross the sea to VALINOR to ask the VALAR for aid, without success. VORONWË was the last to attempt this errand and when all appears lost he turns back and attempts to return to MIDDLE-EARTH. Once the ship reaches sight of land it is wrecked and sinks beneath the waves. ULMO protects VORONWË and brings him alone safely to shore so that he can guide TUOR to GONDOLIN.

******** THE MARGIN OF THE WORLD: Suddenly as if in a distant vision we hear the theme associated with the VALAR, not heard since the appearance of LúTHIEN before MANDOS. It will now begin to take on greater and growing importance.

The Horns of Ulmo* (Scene Five)

A campfire flickers in the darkness. Tuor and Voronwë are seen huddled over it.

TUOR

In a dim and perilous region, in whose great tempestuous ways

I heard no sound of men’s voices—in those eldest of days

I sat on the ruined margin of the deep-voiced echoing sea

whose endless roaring music crashed in foaming harmony

on the land besieged for ever in an aeon of assaults

and torn in towers and pinnacles and caverned in great vaults;

and its arches shook with thunder and its feet were piled with shapes

riven in old sea-warfare from those crags and sable shapes.

Then the immeasurable hymn of Ocean I heard as it rose and fell

to its organ whose stops were the piping of gulls and the thunderous swell;

heard the burden of waters and the singing of the waves

whose voices came on forever and went rolling to the caves

’twas a music of uttermost deepness that stirred in that profound

and the voices of all Oceans were gathered in the tumult as the Valar tore the earth

in the darkness, in the tempest of cycles ere our birth;

till the tides went out and the wind died and all sea-music ceased,

and I woke to silent caverns and empty sands and peace.

The campfire dies down. Slowly a cold and bitter morning dawns. The camp is pitched below a mountainside. Voronwë rises and looks out towards the foothills, but Tuor remains huddled in his cloak for warmth.

TUOR

Fell is this frost; and death draws nigh to me, if not to you.

Have I escaped the mouths of the sea, but to lie under the snow?

VORONWË

Short is the sight of mortal men**!

Here is the mouth of the Dry River***, and this is the road we must take.

They rise and advance slowly towards the mountains; darkness falls about them, as if they had entered a deep cleft.

TUOR

If this is a road, it is an evil one for the weary.

VORONWË

Yet it is the road to Turgon.

TUOR

Then all the more do I wonder, that its entrance lies open and unguarded.

I had looked to find a great gate, and strength of guard.

VORONWË

It is indeed strange, that any incomer should creep thus far unchallenged.

I fear some stroke in the dark.

ECTHELION [the voice comes from total darkness, and the challenger is not seen]

Stand! stir not! or you will die, be you foes or friends.

VORONWË

We are friends.

ECTHELION

Then do as I bid.

* THE HORNS OF ULMO: This verse derives from a very early poem of Tolkien’s, which he only incorporated into the tale of Middle-Earth at a much later date as a song chanted by TUOR to his son EäRENDIL. Here however we find it employed as TUOR narrates to VORONWË his encounter with ULMO.

** THE EAGLES: VORONWË has seen in the distance the EAGLES who guard the location of GONDOLIN; their theme is briefly heard.

*** THE DRY RIVER: The DRY RIVER is the path that lead to the HIDDEN WAY and the gates of GONDOLIN

The Message (Scene Six)

A light is struck in the darkness; Ecthelion is seen holding a lantern and closely inspecting the faces of Tuor and Voronwë.

ECTHELION

This is strange in you, Voronwë. We were long friends.

Why do you set me thus cruelly between the law and my friendship?

If you had led hither unbidden another of the elven houses, that were enough.

But you have brought to knowledge of the Hidden Way a mortal man,

and as one of alien kin I should slay him.

VORONWË

Often shall the wanderer return than he set forth.

What I have done, I have done under command greater than the law of the Guard.

The King alone should judge me, and him that comes with me.

TUOR

I am Tuor son of Huor of the House of Hador and the kindred of Húrin;

and these names, I am told, are not unknown in the Hidden Kingdom.

ECTHELION

And you are come to its Gate.

Know then that no stranger who passes it shall ever go out again,

save by the door of death.

He holds up the lantern, and a great golden Gate is seen outlined in the darkness.

TUOR

Speak not ill-boding! If the messenger of the Lord of Waters go by that door,

then all who dwell here shall follow him.

Lord of Fountains, hinder not the messenger of the Lord of Waters*!

He raises his hand towards the Gate, which at once swings open before him to reveal the high Tower of Gondolin as in Scene One.

ECTHELION [in awe]

Now no further proof is needed; and even the name that he claims matters less than this clear truth: that he comes from Ulmo himself.

Turgon enters to meet Tuor with Idril on his right and Maeglin on his left.

TURGON

Rejoice that ye have found the Hidden City,

where all who war with Morgoth may find hope.

Gondobar, City of Stone, it is called, and the City of the Dwellers in Stone;

Gondolin, the Stone of Song and Tower of Guard**.

TUOR

Behold, O Lord of the City of Stone,

I am bidden by the one who makes deep music in the abyss,

and who knows the minds of elves and men:

the Days of Release*** draw nigh.

Therefore I have been brought to you,

to bid you number your hosts and prepare for battle; for the time is ripe.

TURGON

That I cannot do; for I will not adventure my people against the fires of Morgoth.

TUOR

Hear the words of the Lord of Waters!

The Curse of Mandos hastens to its fulfilment,

and all the works of the Eldar shall perish.

Abandon therefore this fair and mighty city that you have built,

and go down to the sea.

TURGON

The paths of the Sea are forgotten, and the highways faded from the world.

Enough of my people have gone forth into the wide waters never to return,

and have perished in the deeps or wander now lost in the trackless shadows.

It may come to pass that the Curse of Mandos shall find me too ere the end,

and treason awake within these walls; but only then will they be in peril of fire.

I have spoken.

He turns from his throne above the City and leaves. Tuor alone remains at the front and sinks slowly to his knees, weeping in despair. Idril comes forward to succour him, and Tuor looks into her eyes; but this time she does not draw back, but seizes his hands in a fervent and loving embrace. Maeglin, alone at the back of the stage, looks on with a jealous eye.

* TUOR’S MISSION: During this passage the orchestra reinforces TUOR’s declaration of his identity with a progressive series of themes associated with his mission: the CURSE OF MANDOS, the HOUSE OF HADOR, the bidding of ULMO, and finally (as he reveals his armour and the Gate swings open before him) the archaic theme describing the heritage of GONDOLIN.

** THE OTHER NAMES FOR GONDOLIN: We have already heard GONDOLIN referred to as the Hidden City but here TURGON gives all of its names as a welcome to TUOR.

*** THE DAYS OF RELEASE: A hope of redemption and salvation; the phrase is used by Tolkien in his original text for The Fall of Gondolin, but is otherwise unexplained.

The Wedding of Tuor and Idril* (Scene Seven)

The high Tower of Gondolin; views stretch out on all sides. Tuor and Idril, now married with a baby son Eärendil, provoking the unspoken jealousy of Maeglin, stand side by side watching the evening fall. The room stands empty;

Tuor is looking to the west.

TUOR

There elven lights still lingering lie on grass more green than in gardens here,

on trees more tall that touch the sky with swinging leaves of silver clear.

While world endures they will not die, nor fade nor fall their timeless year,

as moon unmeasured passes by o’er mead and mount and shining mere.

When endless eve undimmed is near, o’er harp and chant in hidden choir

a sudden voice uprising sheer in the wood awakes the wand’ring fire.

IDRIL

With wand’ring fires the woodlands fill; in glades forever green it glows.

In a dell there dreaming niphredil** as star awakened gleaming grows,

and ever-murmuring musics spill; for there the fount immortal flows,

its water white leaps down the hill by silver stairs. It singing goes

to the field of the unfading rose where, breathing on the growing briar,

the wind beyond the world’s end blows to living flame the wand’ring fire.

TUOR

The wand’ring fire with quickening flame of living light illumines clear

that land unknown by mortal name

beyond the shadows dark and drear and waters wide no ship may tame.

IDRIL

To haven none his hope may win through starless night his way to steer.

Uncounted leagues it lies from here, in wind on beaches blowing free

’neath cliffs of carven crystal sheer the foam there flow’rs upon the Sea.

BOTH

O Shore beyond the Shadowy Sea! O Land where still the Valar be!

O Haven where my heart would be! The waves still beat upon thy bar,

the white birds wheel; there flowers the Tree! Again I glimpse them long afar

when, rising West of West, I see beyond the world the wayward star,

than beacons bright in Gondobar more fair and keen, more clear and high.

O Star, that shadow may not mar! nor ever darkness doom to die.

They embrace deeply. Slowly the light fades and total darkness covers the scene.

* WEDDING MARCH: The bells of GONDOLIN echo the theme associated with TUOR which are then developed into a wedding march. The first interlude brings in the theme of IDRIL; the second introduces a new melody which will assume greater significance later. In the duet that follows we hear the fully extended melody of MEN as the Second CHILDREN OF ILÚVATAR.

** NIPHREDIL: A small white flower that first grew in DORIATH upon the birth of LÚTHIEN.

The Betrayal* (Scene Eight)

Total darkness still. In that darkness are heard two voices.

Voice of MAEGLIN

I am Maeglin, son of Eöl who had to wife Aredhel sister of Turgon, the King of Gondolin.

Voice of MORGOTH

What is that to me?

Voice of MAEGLIN

Much is it to you; for if you slay me, be it speedily or slowly,

you will lose great tidings concerning the City of Stone that you would rejoice to hear.

Sudden light falls on the face of Maeglin, possessed with a sharp eagerness.

Slowly this too fades.

* THE BETRAYAL:MAEGLIN, captured by MORGOTH, is threatened with torment; but, betrayed by his unrequited love for IDRIL, he is persuaded to divulge the means by which GONDOLIN can be successfully attacked, upon receiving the promise of IDRIL’s hand after TUOR is killed. The chords associated with the idea of treason underpin his music, and will continue to return afterwards.

The Fall of Gondolin (Scene Nine)

The high Tower of Gondolin is once again revealed. The whole of the force of Gondolin is assembled. Turgon stands on the steps of his throne with Idril and Tuor below on his right hand, Maeglin below on his left, and Ecthelion and Voronwë below again. All stand looking at the starlight gleaming on the mountains, and watch towards the east for the first glow of sunrise*.

FULL CHORUS

Ilu Ilúvatar en kárë eldain i fírimoin

The Father made the world for Elves and Mortals

ar antaróta mannar Valion.

And he gave it into the hands of the Lords.

Númessier.

They are in the West.

Eldain er kárier Ithil, nan hildin Úranor.

For Elves they made the Moon, but for Men the red Sun:

Toi írimar!

which are beautiful.

Ilquainen antar annar lestanen Ilúvatáren

To all they gave in measure the gifts of Ilúvatar.

MAEGLIN, VORONWË, ECTHELION and TURGON

Ilu vanya, fanya, eari, imar, ar ilqua ímen.

The world is fair, the sky, the seas, the earth, and all that is in them.

CHORUS

Írima ye Gondobar.

Lovely is Gondobar.

IDRIL, TUOR, MAEGLIN, VORONWË, ECTHELION and TURGON

Nan úye sére indoninya símen, ullume;

But my heart resteth not here for ever;

ten sí ye tielma, yéva tiel are inarquelion;

for here is ending, and there will be an End and fading;

írë ilqua yéva nótina hostainiéva, yallume;

when all is counted and all is numbered at last,

ananta úva táre fárea, ufárea!

but yet it will not be enough, not enough.

ALL VOICES

Man táre antáva nin Ilúvatar, Ilúvatar

What will the Father, O Father, give me

enyárë tar i tyel, írë Anarinya queluva?

in that day beyond end when my Sun faileth?

Suddenly a red light, as of flames, erupts upon the scene. But it comes not from the direction of the sunrise but from the north.

ALL VOICES

Morgoth is upon us!

At once all flee hastily to gather arms. Turgon remains alone upon his throne with Idril and Tuor at his side. Maeglin alone stands apart and brooding.

TURGON [pale and shaken]

Evil have I brought upon the City of the Flower of the Plain in despite of Ulmo,

and now he leaves me to wither in the fire.

Great is the fall of Gondolin**.

TUOR

Gondolin stands yet, and Ulmo will not suffer it to perish!

TURGON

Hope is no more in my heart for the City,

but the Children of the One shall not be worsted for ever.

Many of the people re-enter, fully armed.

TURGON

Fight not against doom, O my people!

Seek those who may safety in flight, if there be yet time;

but let Tuor have your loyalty.

TUOR

Thou art King!

TURGON

Yet no blow will I strike more. Let Tuor be your guide and chief.

But I will not leave my City; I will burn with it rather.

ECTHELION

Lord, who are we if you perish?

TURGON

If I am King, obey my words; and dare not parley further with my commands!

ECTHELION

Here then will I make my stand, if Turgon goes not forth!

He rushes down with many of the others and noises of battle are heard offstage. Turgon slowly advances towards the highest point of the Tower, and stands looking down on the destruction of the City. Idril makes to move after him, but Maeglin moves slowly towards her and seizes her by the arm. She turns with a look of horror and shrinks back; Tuor turning sees them, and rushes on Maeglin. There is a brief struggle. Tuor brings Maeglin to the brink of the precipice, and casts him over***.

IDRIL [turns to look upwards at the unmoving Turgon, and shrieks]

Ah! woe is me, whose father awaits his doom upon his topmost Tower!

TUOR

Now will I get your father hence, be it from the Halls of Angband!

IDRIL

My lord! my lord!

There is a sudden burst of flame from below, and Turgon falls into the abyss.

UNSEEN VOICES

The fume of the burning, and the stream of the fair fountains

withering sere in the flame of the dragons of the North,

fell upon the vale in mournful mists.

Behind the throne the dreadful shadow of the Balrog arises. Tuor and Idril turn and flee, when suddenly through the smoke and ruin Ecthelion appears and stands alone confronting the Balrog. Suddenly he rushes forward and hurls himself towards the Spirit of Flame. With a great cry both fall to oblivion in the abyss. With the fall of the Balrog a sudden darkness descends on the scene and the fires die rapidly down.

UNSEEN VOICES

Then a green turf came there, and a mound of yellow flowers

amid the barrenness of stone, until the world was changed.

Darkness has now totally covered the scene****.

* THE GATES OF SUMMER: The whole of the people of GONDOLIN are gathered to welcome the arrival of summer and greet the dawn; but in the event the light which breaks will come not from the expected sunrise in the east, but from the fires of the dragons of MORGOTH coming from the north.

** GREAT IS THE FALL OF GONDOLIN: It is only now, and too late, that TURGON realises that his pride in the strength of GONDOLIN was false, and that the CURSE OF MANDOS has now finally come to rest on him also. He determines to die with his city, and authorises TUOR to assume his authority and lead his people forth in flight.

*** DEATH OF MAEGLIN: In the original version of the story, MAEGLIN is killed by TUOR when he is trying to throw the infant EäRENDIL from the battlements. At this point in the music we hear a new theme for EäRENDIL which will later assume greater importance in The War of Wrath.

**** THE FATE OF GONDOLIN: The rising theme associated with the destiny of GONDOLIN finally leads to a solo violin meditation on the theme of the wedding march.

The Last Ship (Epilogue)

The shores of the Great Sea, as in Scene Four. A dim and misty day, with a shadowy boat seen in the distance. A now aged Tuor and un-ageing Idril stand alone by the shore.

TUOR

I know a window in a western tower that opens on celestial seas;

from wells of dark behind the stars there ever blows a keen unearthly breeze.

Its feet are washed by waves that never rest.

There silent boats go by into the West

all piled and twinkling in the dark with orient fire

with many a hoarded spark that divers won in waters of the rumoured sun.

DISTANT FEMALE VOICES

Man kenuva fáne kirya

Who shall see a white ship

Métima hrestallo kira,

leave the last shore,

i fairi néke ringa súmaryasse

the pale phantoms in her cold bosom

ve maiwi yaimië?

like gulls wailing?

TUOR

There sometimes throbs below a silver harp,

touching the heart with sudden music sharp;

or far beneath the mountains high and sheer

the voices of grey sailors echo clear

afloat amid the shadows of the world

in oarless ships and with their canvas furled,

chanting a farewell and a solemn song;

for wide the sea is, and the voyage long.

DISTANT FEMALE VOICES

Man tiruva fána kirya,

Who shall heed a white ship,

wilwarin wilwa, ëar-kelumessen

vague as a butterfly, in the flowing sea

rámainen elvië, ëar falastala,

on wings like stars, the sea surging,

winga hlápula rámar sisílala,

the foam blowing, the wings shining,

kale fifírula?

and the light failing?

The shadowy ship draws close into the shore. Tuor embraces Idril, and enters the ship. At once through the mists the ship sets sail into the Ocean and slowly draws away as Idril stands alone looking after it.

IDRIL

O happy mariner, upon a journey far beyond grey islands far from Gondobar

to those great portals on the final shores where faraway constellate fountains leap

and, dashed against Night’s dragon-headed doors in foam of stars,

fall foaming in the deep!

DISTANT MALE VOICES

Man hlavula rávëa sure ve tauri lillassië,

Who shall hear the wind roaring like leaves of forests,

ninqui karkar yarra isilme ilkalasse,

the white rocks snarling in the moon gleaming,

isilme píkalasse, isilme lantalasse ve loikolíkuma:

in the moon failing, in the moon falling like a corpse-candle:

raumo narrua, undume rúma?

the storm rumbling, the abyss moving?

IDRIL

While I look out alone behind the moon

imprisoned in the white and windy tower,

you bide no moment and await no hour

but go with solemn song and harpers’ tune

through the dark shadows and the shadowy seas

to the lost land of the Two Trees*,

whose fruit and flower are Moon and Sun,

where light of the earth is ended and begun.

DISTANT MALE VOICES

Man kenuva lumbor ahosta menel akúna

Who shall see the clouds gather,the heavens bending

ruxal’ ambonnar, ëar amortala,

on crumbling hills, the sea heaving,

undume hákala, enwina lúme elenillor pella

the abyss yawning, the old darkness behind the stars

talta-taltalar atalantëa mindonnar?

falling upon fallen towers?

Great lights begin the shine through the mists, as of a shower of golden water.

UNSEEN VOICES

You follow Eärendil without rest, the shining mariner beyond the West

who passed the mouth of night, and launched his bark

upon the seas of everlasting dark.

DISTANT VOICES

Man tiruva rákina kirya ondolisse morne

Who shall heed a broken ship on the green rocks

nu fanyare rúkina, anar púrëa tihta

under red skies, a bleared sun blinking

axor ilkalannar métim’ auresse?

on bones gleaming in the last morning?

IDRIL and UNSEEN VOICES

Here only long afar, in tears of pain, I glimpse the flicker of the golden rain

that falls forever on the outer seas beyond the country of the shining Trees.

DISTANT VOICES

Man kenuva métim’ andúne?

Who shall see the last evening?

As the lights through the mists grow ever stronger, the curtain slowly falls.

* THE TWO TREES: The theme associated in Fëanor with the destruction and loss of the TWO TREES reappears for the first time since that event, but now assuming a mood of triumph.